Peace as a Creative Act和平作为一种创造性的实践

- Jul 28, 2024

- 7 min read

After more than 5 months of traveling across Europe and Asia, I recently reached Shanghai safe and sound. Unharmed and on my own bicycle. Notwithstanding some risky situations, I haven’t been stopped, ambushed or kidnapped. My stuff hasn’t been stolen. I didn’t get sick. I reached China in peace.

经过五个多月跨越欧亚的骑行,我终于安全抵达上海。尽管经历了一些风险和挑战,但我从未遇到抢劫、伏击或绑架。我的行李也没有丢失,身体健康,顺利到达中国。

And yet I can't escape the feeling of having barely escaped conflict, violence, and even war. Or did I really, after all?

然而,我总有一种感觉,仿佛我仅仅是勉强躲过了冲突、暴力,甚至战争。或者说,我真的躲过了吗?

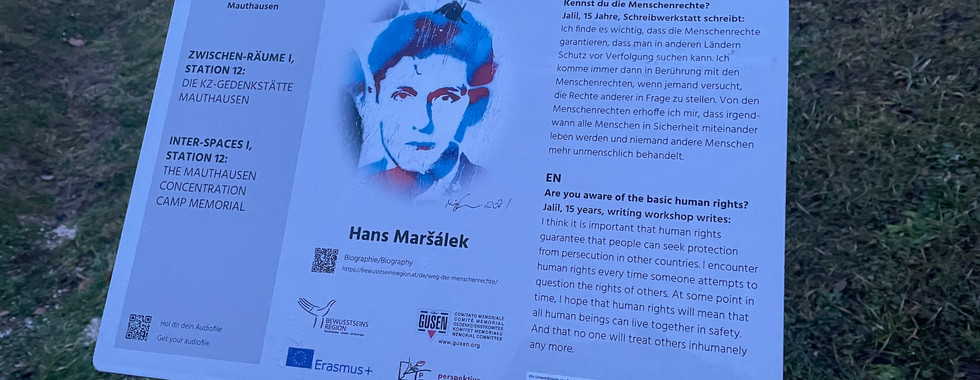

In Western Europe all the way to Vienna, I traversed several guilty landscapes from the Second World War and Holocaust, which reverberations recently have come back in full force with the West taking side with Israel as if its a moral duty to do so.

在西欧,一直到维也纳,我穿越了多个二战和大屠杀的历史遗迹。最近,这些历史的余波重新涌现,西方国家似乎将支持以色列视为一种道德义务。

In Eastern Europe, traumatic traces of the Cold War and the resurgence of nationalist narratives were very visible.

在东欧,我清晰地感受到冷战遗留下来的创伤和民族主义叙事的复兴。

Arriving in the Middle East, and hence the Islamic countries, people increasingly wanted to talk about the plight of their fellow Muslims, especially the Palestinians, whose destruction they could follow live on screen every day.

抵达中东地区,也就是伊斯兰国家后,人们越来越关注他们同胞穆斯林,特别是巴勒斯坦人的困境。每天,他们都能通过屏幕实时看到巴勒斯坦所遭受的灾难。

In Iran, this general sense of injustice became very specific with the outburst of conflict on the brink of war, with people being torn between sadness and anger, seeking comfort and consolation in art and literature.

在伊朗,这种普遍的不公感在冲突接近战争边缘时变得尤为具体。人们在悲伤和愤怒之间挣扎,在艺术和文学中的寻找安慰与慰藉。

In the Central Asian countries, the memories of being ruled by foreign forces were very fresh. I also met Russians who were hiding from war and the consequential potential conscription to fight in it.

在中亚国家,人们对曾经被外来势力统治的记忆依然历历在目。我还遇到了一些因逃避战争和可能被征召入伍而流亡的俄罗斯人。

In China, I rode through a surreal situation of a peaceful and extremely beautiful place that the western world has deemed the stage of a cultural oppression.

在中国,我穿越了一个令人难以置信的景象:一个和平而极其美丽的地方,却被西方世界视为文化压迫的象征。

And in Eastern China, I was surrounded by people who increasingly face the woes of a Western world turning its back to their country. As a foreigner they easily could have blamed me for it. But they didn’t. On the contrary. They were glad to meet someone visiting and learning from China.

在中国东部,我看到越来越多的人面临西方世界逐渐疏远他们国家的困境。作为外国人,我本可以被视作这种态度的替罪羊。但实际上,他们并没有这样做。相反,他们很高兴能见到我这个来中国参观和学习的人。

Given this turmoil and strife on the world stage, wasn’t I lucky to make it to Shanghai unharmed?

在世界局势如此动荡不安的背景下,我能安全抵达上海,难道不算幸运吗?

Maybe there was something else besides luck that helped me through: the will, if not people’s natural inclination towards peace.

也许,除了运气,还有其他因素帮助我顺利完成旅程,那就是意志,或者说是人们对和平的渴望。

At the very beginning, I made a stop at a peace monument: the Lion’s Mound in Waterloo, overlooking Napoleon’s last battlefield, watching over any new imperial ambitions France may even summon again.

在旅程伊始,我曾停驻足于和平纪念碑前:滑铁卢的狮子山。从这里可以俯瞰拿破仑最后的战场,时刻警惕任何可能重新燃起的法国帝国野心。

I saw Martin Luther on his pedestal in Worms, a cartouche stating that peace of mind is much more important than orthodoxy.

我在德国沃尔姆斯市看到了马丁·路德的雕像,铭文上写着:心灵的平静比教条正统更为重要。

I followed the Danube that now connects many countries it once divided, even taking some ferries on lazy afternoons.

我沿着多瑙河前行,这条曾经将许多国家分隔开的河流,如今将它们连接在一起。在慵懒的下午,我还乘坐了几次渡轮。

As soon as I went beyond the enforced boundaries of Fortress Europe, I began to explore a large non-western psychological repertoire of alternatives to the practice of ignoring, judging, competing, or even fighting the zero-sum games of global politics.

一旦我越过了“欧洲堡垒”的封闭边界,我开始探索一种非西方的心理范式,这种范式提供了应对全球政治零和博弈的另类方式——它们不仅仅是忽视、评判、竞争,甚至是对抗。

In Türkiye, the first word that caught my attention was “welcome” (hosgeldiniz). I saw it so many times along the road, I decided to look it up.

在土耳其,第一个引起我注意的词是“欢迎”(hosgeldiniz)。沿途看到这个词无数次后,我决定查一下它的含义。

In Iran, I was enthusiastically introduced to the Sufi poetry of love from ancient poets like Shams Tabrizi and his student Rumi, masters in finding words for the essentials of human affection.

在伊朗,我被热情地介绍了苏菲诗人沙姆斯·塔布里兹和他的弟子鲁米的爱情诗。他们是用词汇表达深刻人类情感的艺术大师。

In Uzbekistan, the national narrative turned out to revolve largely around keeping the peace with the mighty neighbours of India, Russia, the European Union, and China, with in its National Museum a remarkable display of the Uzbek president shaking hands with other leaders.

在乌兹别克斯坦,我发现国家叙事主要围绕着如何与强邻印度、俄罗斯、欧盟和中国保持和平。国家博物馆里展示了一系列乌兹别克斯坦总统与这些领导人握手的珍贵照片。

Upon the border of Kyrgyzstan, I was quickly permitted entry to the country when I replied to the question of the purpose of my visit that I wanted to visit the Suleiman Too, or the Throne of Solomon, the wise king from the Old Testament and the Quran, who was a master of reconciliation between humans and between humans and nature. A cyclist with such intentions, welcome my friend.

在吉尔吉斯斯坦边境,当我回答入境目的时,说我想参观苏莱曼托(Suleiman Too),即所罗门的宝座——这位在《圣经》和《古兰经》中被称为人类与自然之间和解的智慧之王时,我很快获得了入境许可。一个有这样的意图的骑行者,欢迎你,我的朋友。

And in China I followed the traces of centuries of disseminated Buddhism and its ideas about seeking Enlightenment and inner peace, before arriving into the heartlands of Daoism and Confucianism, values systems different in inspiration, but alike in their emphasis on social harmony as something to work for and accomplish over time.

在中国,我追溯了佛教几百年来的传播足迹,体会到追求启迪和内心平静的理念,随后进入了道教和儒家思想的核心地带。这些价值体系虽然在灵感来源上各有不同,但它们在强调社会和谐的追求上却有着相似之处,都是通过时间的积累和不懈努力来实现的。

With these recent experiences, I came to understand much more deeply the difference between concepts of peace in the West and those in the East. Maybe no wonder. In the Roman languages, peace comes from "pax" or "pag," which means the lack of war. More precisely, it refers to the time between wars. It’s the negative of war, so to speak. Another word coming from the same etymology is “pay,” as something that averts war. Paying your due means basically paying off war. War is a normality you may succeed to avoid. Or may not succeed. Deep down in the word Peace there is an acceptance of its temporariness.

通过这些经历,我对东西方和平的不同概念有了更深刻的理解。这也许并不令人意外。在罗马语系中,“和平”源自于“pax”或“pag”,意味着战争的缺席。更确切地说,它指的是战争之间的时光。可以说,和平是战争的对立面。另一个相同词源的词是“pay”(支付),即防止战争的手段。支付欠款基本上就是偿还战争。战争是一种可能会被避免的常态,或者可能无法避免。从根本上讲,“和平”这个词隐含了对其暂时性的接受。

Compare this with the Chinese word for peace: 和平/HePing. In a previous blog, I already shared with you the origins of the word “和/He," in which people and food come together as the essence of social harmony. In turn, the addition of “平/Ping" extends this this concept by incorporating the notion of balance, as represented in the character for Ping: 平, a human figure lifting its arms, holding a beam in balance. HePing as a value not only presupposes the presence of food and humans but also fair social distribution. To achieve this, a constant positive effort needs to be made. Peace in this Eastern version, is a creative act, not the negative of war. Making peace is an art that requires at least wisdom and modesty. Peace is hard work too.

与此相比,中文的“和平”(HePing)则展现了不同的内涵。我在之前的博客中已提到“和”(He)的来源,它体现了人和食物的结合,象征社会和谐的本质。而“平”(Ping)的加入进一步延伸了这一概念,加入了平衡的意义。字形中的“平”字表现了一个人形举起双臂,保持平衡的姿态。作为一种价值观,“和平”不仅包括了食物和人的存在,还强调了公平的社会分配。要实现这一点,需要不断的积极努力。在东方的理解中,和平是一种创造性的行为,而不是战争的反面。实现和平是一门艺术,需要智慧和谦逊,并且需要艰苦的付出。

So here is my speculation: It may be the complete lack of these wisdoms in current Western mainstream thinking, that inhibits any idea of pursuing peace in the West, even sometimes demonises anyone who does, and facilitates the growing distrust and feeling that once again a debt needs to be paid. By the others, of course.

所以,我有这样的猜测:也许正是因为当前西方主流思维中缺乏这些智慧,才阻碍了西方追求和平的理念,甚至有时会妖魔化那些追求和平的人。这种缺乏智慧还助长了日益增长的不信任感,以及对“还债”的感觉——而这些“债务”,自然是由其他人来承担的。

Comments